- FAQs

- |

Completing a Residency

The military residency application process for aspiring military physicians is different than it is for civilian ones, specifically the application process, Match Day and, of course, the fact that you will be an officer with a military rank, not a civilian.

Day In The Life

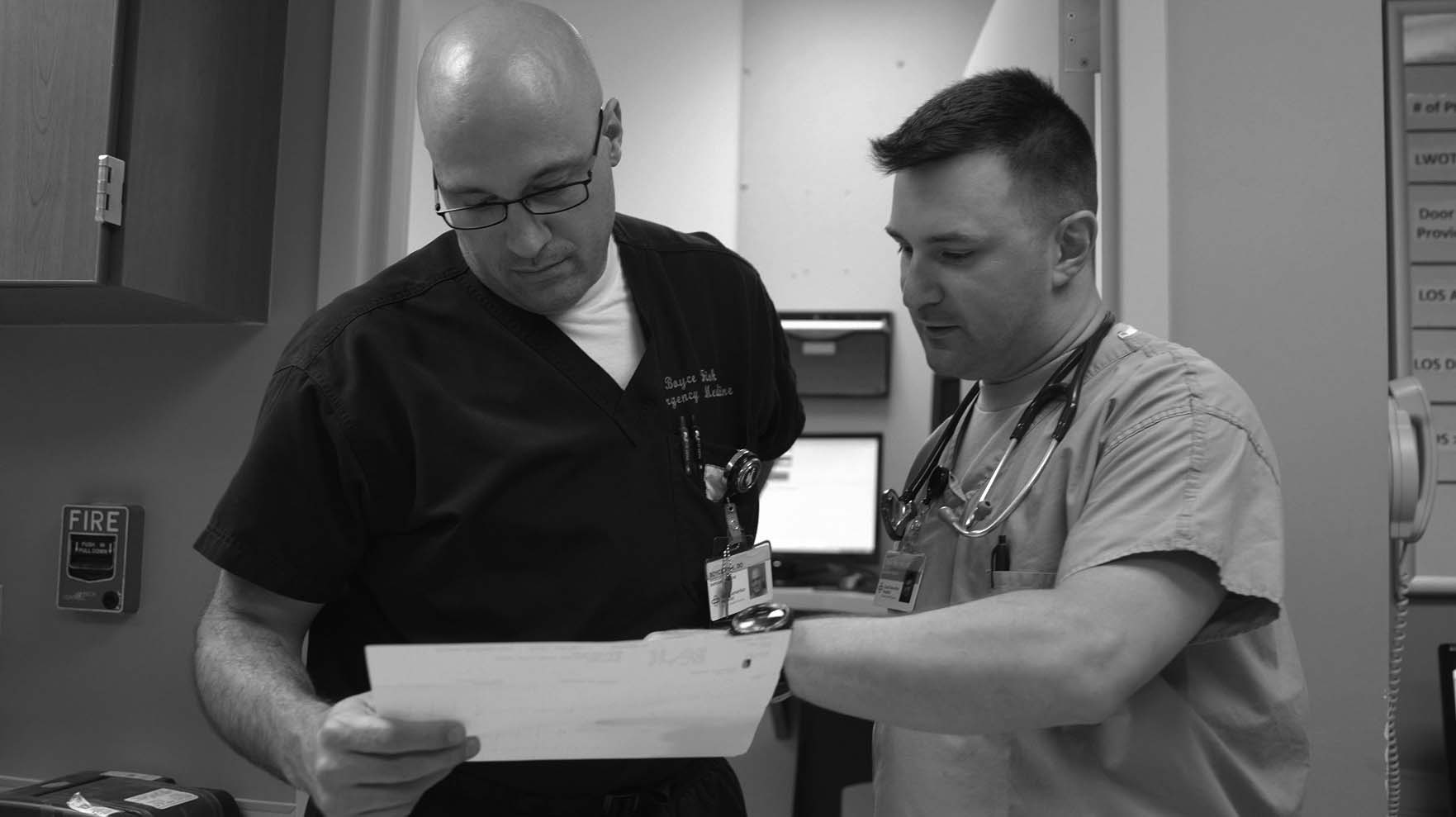

John Trentini shows the fast-paced nature of emergency medicine during his shift at a civilian hospital.

John Trentini, M.D., Ph.D.

Emergency Medicine Resident, Air Force

Emergency Medicine Residency Overnight Shift

John's day-to-day medical service is very similar to his civilian colleagues. He goes on rotations, is mentored by attending physicians and receives on-the-spot training. During his overnight shift at Good Samaritan Hospital, John sees a patient who he puts on cardiac alert. The fast-paced, unexpected nature of emergency medicine is preparing him for a career in the Military.

TRENTINI: Being an emergency medicine resident, we train in the most part in civilian hospitals — from the Air Force’s perspective is to train a good emergency department physician.

TRENTINI: So it’s about — about ten to 11:00 or so now, so getting ready to start our night. Kind of always take a peek at all the rooms, see what’s going on in the way in. These are some of the higher-acuity rooms, so if there’s anybody that’s real sick that needs some help right away, I can always peek in, but everybody looks pretty stable right now. So we’re getting checked in and settled in here. Hi, sir.

PATIENT: Hi.

TRENTINI: I’m Dr. Trentini. Nice to meet you.

PATIENT: Nice to meet you.

TRENTINI: I’m going to just shake this hand, they’re working on you over there. What brings you in tonight?

PATIENT: I’ve — chest pain. A really bad pressure right here. And I can feel it all the way down my left arm.

TRENTINI: OK.

PATIENT: It’s almost like somebody’s sitting on my left shoulder.

TRENTINI: OK.

PATIENT: Real bad pressure.

TRENTINI: When did it start?

PATIENT: About — about two hours ago.

TRENTINI: OK.

PATIENT: It started out real slow, and it just got gradually worse and didn’t go away like normal.

TRENTINI: OK. Hey, Dr. Fish? FISH: Hey.

TRENTINI: I’ve got a gentleman that I just put a cardiac alert out on. He is stable, but here’s his EKG. So, I mean, he’s got some ischemic changes here in V2, V3, V4. He’s probably having an anterior wall MIT. Yeah, so when you’re working with an attending, basically you’re working under their supervision, and so for me, I try to practice independently. In my mind, I pretend like they’re not there. So I’m on my own, and I need to make all the medical decisions. But in the back of my mind I know that they’re there, and they’re watching me, and they’re — they’ve got my back.

FISH: His cardio back yet?

TRENTINI: Not yet, we just put out the cardiac alert, so — so I’ll take a look at his chest ray, we’ll push with 5,000 to heparin, put him on a heparin drip, we’ll start him on a nitro drip, his pressures will tolerate it — his pressure’s been 190 throughout, so.

FISH: Alright.

TRENTINI: And then we’ll get his pain — pain under control.

FISH: Alright, so we’re going to get things taken care of, alright?

PATIENT: Thank you.

TRENTINI: Alright. Alright, sir. I’ll come and check on you in a bit, OK? Let me go and put it — talk to Chuck and get your medicines ordered, OK?

PATIENT: Thank you.

TRENTINI: Alright. Emergency medicine, in my opinion, is the best medical specialty because it’s the most interesting, it’s the most fun — you’ve got to be on your toes — and you take care of people that are pregnant and take care of babies all the way up to 100-year-old patients, with a wide variety of illnesses and a wide variety of acuity as well. So it’s fun, and it’s fast-paced, and so you get to see a lot of people on a shift and you get to see a lot of different things on a shift.